This information has been written for our website by Dr. Rocío Acuña Hidalgo, MD PhD Molecular Geneticist and Member of our Scientific and Medical Advisory Board

What is our risk of having another child with Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome?

One of the most important questions for couples with a child diagnosed with Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome is to understand what is their risk of having another child with the same disease. This is known as “recurrence risk”.

Parents who have a child with Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome are typically counselled that their recurrence risk is very low, with the risk of having another child with the same disorder at less than 1 in 100.

Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome is always caused by new mutations in the SETBP1 gene

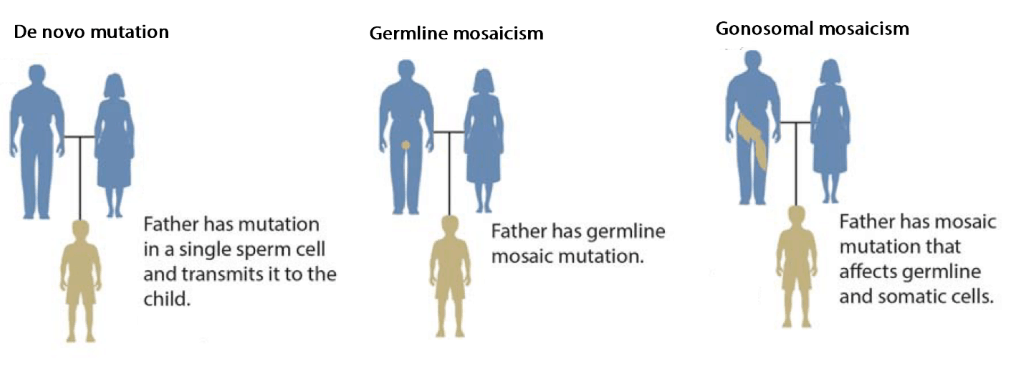

Genetic tests for Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome (SGS) will usually find the disease-causing mutation in the blood or saliva of the child with SGS but not in the blood or saliva of the parents. This is because the genetic mutation that causes SGS is not in the cells of the parents’ body, but appears for the first time either in the father’s sperm cell or in the mother’s egg cell. During fertilization of an egg by a sperm cell, if either the sperm or the egg cell has the mutation that causes SGS, the baby will have the genetic mutation and will be born with SGS.

Because the disease-causing mutation appeared for the first time in the father’s sperm cell or mother’s egg cell by chance, it is very unlikely that the mutation appears a second time by chance. This is why couples with a child who has SGS are counseled that the risk of recurrence is very low. Additionally, other members of the family (such as parents, siblings or other children of the couple with a child with SGS) do not have additional risk of having a child with SGS.

Recurrence risk and mosaicism for the mutation that causes SGS

In very rare cases, couples have been reported to have more than one child born with SGS. This can be a source of concern for parents who have a child with SGS and are thinking about having more children.

Couples who have more than one child with SGS have germline or gonadal mosaicism for the mutation that causes SGS. Germline or gonadal mosaicism means that the genetic mutation that causes SGS appeared in more than one sperm cell in the father or more than one egg cell in the mother. Couples who have germline or gonadal mosaicism, have a higher risk of recurrence; the genetic mutation that causes SGS can still be found in one of the sperm or egg cells of the parents, which could lead to a second child being born with SGS. The risk of recurrence depends on the degree of germline mosaicism (i.e. how many sperm or egg cells there are with the genetic mutation). In even rarer cases, the genetic mutation can also be found in blood of the parents, even if the parent has no signs or symptoms of SGS. This is known as “gonosomal mosaicism” and recent research suggests that for these couples, the risk of recurrence is also higher.

Please note: this example above uses the father for illustration purposes only, but it could equally be the mother who had a de novo mutation in a single egg cell, who has germline mosaicism or who has gonosomal mosaicism, resulting in a child with SGS.

Summary

The recurrence risk for most couples with a child diagnosed with SGS is very low (<1%). Couples with a child diagnosed with SGS and who would wish to have more children but are concerned about their risk of recurrence should discuss their options with a genetic counselor (e.g. early prenatal diagnosis).

On rare occasions, couples may have germline or gonosomal mosaicism for the mutation that causes SGS, which increases their recurrence risk. Unfortunately, currently there is no way to know whether a couple has germline mosaicism. However, couples can be tested for gonosomal mosaicism by trying to detect the disease-causing mutation in the blood of the parents. If the disease-causing mutation is found in the parents’ blood, the risk of recurrence is higher.

Note:

Detection of parental gonosomal mosaicism needs to be carried out with Next Generation Sequencing and not with Sanger Sequencing (please refer to Rahbari et al. Timing, rates and spectra of human germline mutation, Nature Genetics 48, 126–133(2016)

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.3469 or https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30665023.pdf).

Newsletter Signup

Sign-up to receive family stories and updates on our research projects and fundraising campaigns.